Hi guys! I chose to write my reflective essay on Francisco Goya and the influence of the Grotesque on his artwork across his career. I love this type of art so I hope you guys enjoy!

When you hear the words “art history,” what is the first thing that comes to mind? Is it the floral, ornate, airy scenes of a Rococo scene or maybe a prehistoric cave painting with thousands of years of history tied up in an amazingly simple image. If you are like me, those two words prompt feelings of dread for the imminent boredom that comes with staring at a four-hundred-year-old painting trying painstakingly to connect it to the Catholic church. I thought that I was forever doomed to dislike premodern art and its creators. That is until one day––as I drifted off to the tragic life story of Lord Byron in first period––I was introduced to Francisco Goya. For those of you who are unfamiliar with Goya, he was a Spanish painter and printmaker born in the mid-eighteenth century whose work is emblematic of the Romanticism movement in the nineteenth century.

Goya’s earlier works showcase the fantasy of the earlier Rococo style as he painted for the royal court. Yet toward the end of the 1780s, he fell ill (the exact cause is unknown but syphilis and other venereal diseases are suspects––fitting for a grotesque devolution) and upon his recovery was completely deaf (Felisati & Sperati, 2010). This period signified the start of a descent into a different, twisted style of painting; the fantasy and joy in his work were slowly replaced by dark and grotesque figures.

In Chapter 5 of Bakhtin’s Rabelais and His World, he highlights the differences between the classical and grotesque bodies. Toward the beginning of his career, Goya created several religious paintings and focused on scenes that depicted joyous, content peoples. “La Maja Desnuda” is a portrait of Venus commissioned in ~1795 by Spanish aristocrat and politician Manuel Godoy. The woman in the painting is a characterization of what Bakhtin refers to as the “individual body;” she is elegant and composed, and Goya really focuses on capturing the beauty of his human muse (Rabelais and His World, 321). All the elements that compose a grotesque body are absent: she is thin therefore contradicting the Grotesque, swollen belly, the genitals have little exposure to the viewer of the painting, and, the mouth and the nose are delicate features denying them of the “leading role” (Rabelais and His World, 321). The composition of Goya’s earlier works follows the same principles with a focus on the Godly and virtuous human experience, but shortly after creating “La Maja Desnuda” we can see a change in Goya’s work as it leans toward the Grotesque.

In 1799, Goya published a series of prints titles “Los Caprichos.” They are a morbid and disturbing collection of images that center around death, sex, and perversion of clerical themes and peoples. The abundance of witchcraft and disfigured bodies is far from the delicacy of “La Maja Desnuda.” One of my favorite prints is “Están Calientes,” which translates to “They are Hot.”

We see these three men sitting around a table burning their mouths on food that is––you guessed it––too hot. Personally, I am a fan of the guy on the rightmost of the print who is watching his companions burn themselves a nightmare-inducing smile on his face. The movement in this scene is perfectly captured in its frozen yet chaotic nature and has a certain familiarity to it; just take a walk through the Haverford DC during a meal, and you’ll see the same scenario playing out at any number of tables. It is a perfect combination of grotesque traits that give it depth and allow viewers to identify various complex subtleties. One thing that is definitely not subtle, however, is the prevalence of the mouth in this scene. Above all, the mouth is the most overt and essential element of the Grotesque body. Bakhtin writes:

“But the most important of all human features for the Grotesque is the mouth. It dominates all else. The Grotesque face is actually reduced to the gaping mouth; the other features are only a frame encasing this wide-open bodily abyss” (Rabelais and His World, 317).

Their mouths are not exaggerated in size or unnaturally contorted––yet they are piercing and draw your focus. The pure darkness is a stark contrast from the intricate details that define the face and serves as a focal point that is unrivaled by any other feature of the print. The Grotesque nature of the mouth in this scene are not confined just to their appearance, however. These “gaping mouths” are in the midst of consumption: they continue to eat the hot food on which they burn themselves with a determined, almost insatiable hunger. Bakhtin refers to the mouth as “the open gate leading downward to the bodily underworld” (Rabelais and His World, 325). This characterization lends itself to the hellish imagery of scalding bits of food burning its way through the body on its journey to the stomach and the pain and discomfort we see in the men’s body language. The mouth is the intermediary to swallowing, an “ancient symbol of death and destruction,” and we see here how it lives up to its legacy (Rabelais and His World, 325). They may not have the bulging bellies or profuse expulsion of bodily fluids that encompass the Grotesque, but the men fulfill the element of consumption––and even overconsumption of this unpleasantly hot food.

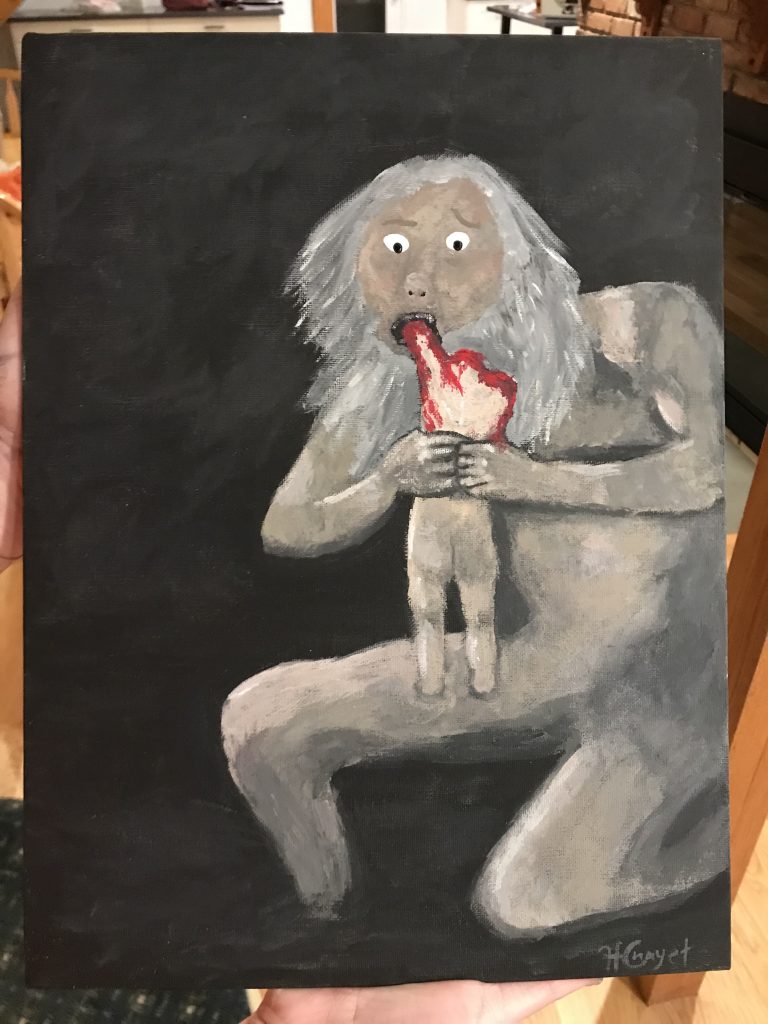

In his later years, Goya’s mental state began to deteriorate, and with that came the creation of a series of murals known as the Black Paintings. The Black Paintings share many of their traits with his “Los Caprichos” style and often center around death and bleak depictions of everyday life. They represent the full extent to which Goya embraced the Grotesque and its influence on his life and his work. I want to leave you all with one of my favorite of his Black Paintings titled “Saturno Devorando a su Hijo” (Saturn Devouring His Son). I will admit, this painting is one of his more graphic and maybe a bit disturbing. But I think its grisly, offputting appearance is exactly what the Grotesque is supposed to be; it is consumption, birth, death, nudity, gore, and even giants.

Hi Hannah,

Thanks so much for sharing this project — a super fascinating (and entertaining!) read. I’ll admit, the only Goya painting I recognized was Saturn Devouring His Son, so I’m really grateful for the exposure to more of his work and some context for that grim scene. It leads me to wonder about the prevalence or fame of the grotesque, and situations wherein an artist or author’s other work can take a backseat to the sort of shock value of some of their other work. Like, I don’t know if Rabelais dabbled in the non-grotesque or pedestrian, but I hardly think we would have a class on “the normative.” Anyway, it’s early (for me) in the morning so pardon the rambling but thank you again for this really cool essay!

Hi Hannah,

This was fascinating! I love watching artists’ styles change as they age/undergo mental changes (with my favorite example being Louis Wain’s paintings of cats becoming more colorful and abstract as his schizophrenia got worse https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Wain ). I also really liked your recreation of Saturn. You got the eyes right.

It is interesting to me how Goya’s art became more and more Grotesque–as you said, by the time he painted Saturn Eating His Son, he was really checking off all the marks of the Grotesque outlined by Bakhtin, even though I doubt Goya read much of him or Rabelais.

Thank you for providing such a helpful and entertaining topic! I was so shocked as I scrolled down from La Maja Desnuda to Están Calientes because I wasn’t expecting the change to be this big! In the whole process, Goya gradually moved from the beauty of the classical body to the posture of the ordinary body, and finally, to the grotesque body, I wonder whether this change of style had something to do with his loss of hearing. I noticed that from the three paintings in your post, his focus shifted from individual body shape to group dynamics, and finally to the absolute control of man by God (or maybe nature). And when the overall dynamic in his painting is stronger, the details and refinement are relatively reduced, and the visual impact is thus greater. I am wondering whether this change is related to the political changes and wars he had been through.

Hi Hannah, this is so cool! I love how clearly your passion for this art can be seen throughout the reflection; it makes it a very enjoyable read. I think the entire topic is cool (and love that you included your own painting!!), but I’m going to focus a little bit on the beginning: one thing I’ve been really interested in since the beginning of class is where the absence of the grotesque can be felt the most, so I’m glad that you didn’t just start with Goya’s most grotesque works. It’s cool that you started by showing how his early work conformed heavily with societal/religious expectations, and then slowly transitioned into the grotesque, first with the more nuanced work and then Saturn.

On an unrelated note, I never noticed until now how confused Saturn looks to be doing what he’s doing.