content warning: my project discusses anti-Semitic imagery and stereotypes

Hey everybody! I have been super into the story of Oliver Twist for a long time- ever since 2009, when I played a workhouse orphan in my school’s high school production of the musical Oliver! Before long, my best friend and I had seen several of the film adaptations and attempted on multiple occasions to get through Charles Dickens’ original novel. Oliver Twist centers on an orphan- named Oliver Twist- who escapes from the workhouse he was brought up in and runs away to London where he falls in with a gang of pickpockets led by Fagin, an old man who provides housing and food to the children and sells stolen goods. Oliver gets framed for picking a pocket, but the man who was robbed- Mr. Brownlow- believes that Oliver is innocent and takes him in. Oliver has a pretty sweet life for awhile until he gets kidnapped by Fagin’s gang, who fear that he’ll report them and their location to the police. The rest of the story revolves around Mr. Brownlow trying to get Oliver back, and ultimately he is safely returned. In some versions of the story, Fagin is executed, while in others, he gets away. That summary was super bare bones and doesn’t reflect the whole story and all the characters involved, but these are the major plot points that run through the novel and most adaptations.

What I really enjoy about the story is the vibrant characters and how many of the film adaptations encourage the viewer to question their own sense of morality and to view the characters and the crimes they commit as complex and not so black and white. From taking this course, I have become interested in looking at the story of Oliver Twist through a Bakhtinian lens. To examine Oliver Twist, I read Bakhtin’s chapter five of Rabelais and His World, which focuses on characteristics of the grotesque body. I was interested to see how Rabelais’s use of grotesque realism compares with the way Charles Dickens and subsequent adapters of Oliver Twist use grotesque imagery. The character that I am focusing on in this project is Fagin.

Fagin is the most complex character in Oliver Twist, and different adaptations cast him in different lights. In the novel, Fagin is portrayed as the embodiment of evil. His physical characteristics and attributes such as greed are emphasized. Dickens relies on several anti-Semitic stereotypes in his portrayal of Fagin, and Fagin is rarely referred to by name in the novel. He is called “the Jew” over 300 times, and referred to as “the merry old gentleman,” an English nickname for the devil. Although in the 1867 edition of Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens removed many of the references to Fagin as “the Jew,” the character and how he is described reinforce a lot of the firmly entrenched anti-Semitic stereotypes of the time.

When describing his idea of the grotesque body, Bakhtin writes: “Of all the features of the human face, the nose and mouth play the most important part in the grotesque image of the body; the head, ears, and nose also acquire a grotesque character when they adopt the animal form or that of inanimate objects” (316). In Rabelais, these features appear to empower the characters and the audience, but I find that in Oliver Twist, a lot of these grotesque exaggerations take the form of anti-Semitic stereotypes that ‘other’ characters and pass moral judgement based on nothing more than religion.

This is how Fagin is described when Oliver first encounters him: “some sausages were cooking; and standing over them, with a toasting-fork in his hand, was a very old shrivelled Jew, whose villainous-looking and repulsive face was obscured by a quantity of matted red hair” (Dickens, 87). Red hair was used to denote evil and was a common characteristic in anti-Semitic caricature, dating back to medieval plays where Judas was portrayed with red hair, and Renaissance plays, like Shylock in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice.

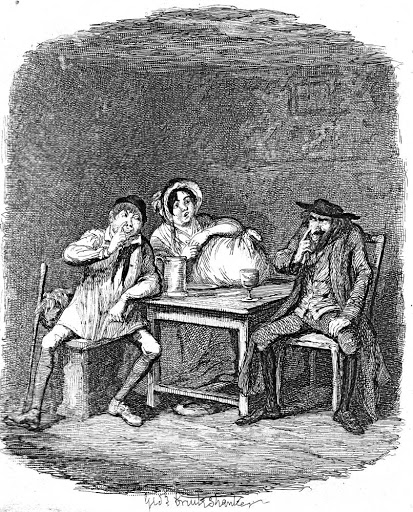

The exaggerated nose is an important part of Bakhtin’s ideas of the grotesque, and it commonly features into anti-Semitic caricatures. In one scene, where Fagin is talking with another thief, he “[follows] up this remark by striking the side of his hose with his right forefinger,- a gesture which Noah attempted to imitate, though not with complete success, in consequence of his own nose not being large enough for the purpose” (Dickens, 368).

Another moment where Fagin is described using anti-Semitic stereotypes is one scene where Dickens describes him walking around at night. He writes: “As he glided stealthily along, creeping beneath the shelter of the walls and doorways, the hideous old man seemed like some loathsome reptile, engendered in the slime and darkness through which he moved: crawling forth, by night, in search of some rich offal for a meal” (171). This description comes out of a medieval stereotype about Jewish people stealing and eating Christian children.

Dickens portrays Fagin as evil incarnate, and there is little room for moral gray area in the novel. Fagin is pure evil, while Oliver is pure goodness. The only character who inhabits any sort of moral gray area is Nancy, a prostitute who is killed after giving Mr. Brownlow information that leads to Oliver’s rescue.

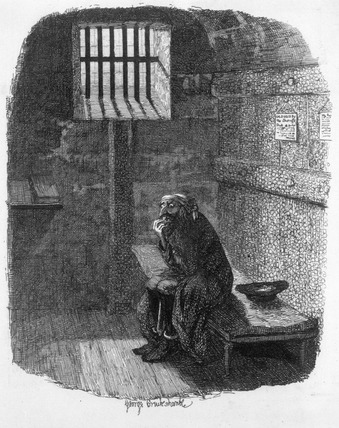

Another interesting aspect of Fagin’s character is how he is treated by various movie adaptations of the novel. Probably the most famous adaptation is David Lean’s 1948 film version. This film probably comes closest to Fagin’s physical description of the novel. Alec Guinness played Fagin in this version, and he puts on a voice and wears a prosthetic nose. The makeup was inspired by the original illustrations accompanying the novel, done by George Cruikshank. The anti-Semitism in the film inspired violent riots in Germany, protesting screenings of the film. The US release of the film was delayed until 1951 because of concerns over how Fagin was portrayed.

Bakhtin writes: “The grotesque body, as we have often stressed, is a body in the act of becoming. It is never finished, never completed; it is continually built, created, and builds and creates another body. Moreover, the body swallows the world and is itself swallowed by the world” (317). This quote reminded me of Fagin and the new life he’s gotten through film adaptations. The 1968 musical transformed Fagin into a much more sympathetic character, while toning down the anti-Semitic aspects of his appearance. While no adaptation has fully eliminated the anti-Semitic roots of the character, many adaptations cast Fagin in a sympathetic light and explore his humanity and why he acts in the way he does. The treatment of Fagin reminds me of how Shylock from The Merchant of Venice- another villain with anti-Semitic roots- has come to be a more sympathetic and understood character. Just like Bakhtin’s conception of the grotesque body, Fagin’s body is in the act of becoming. He is constantly changing and evolving, from adaptation to adaptation, and through this new life that he gets in film adaptations, he is given the complexity that he lacks in the original novel.

Hi Charlotte!

This is a really amazing project! I was also in a production of Oliver around 2009, so I grew up obsessed with the show as well. I cannot tell you how many times I watched the 1968 musical movie (that and the 1998 Cats). I really liked your integration of medieval stereotypes into this essay, as well as the references to Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. I also did not know that Dickens revised Oliver Twist in 1867, which was really interesting to learn.

This was a wonderful engagement and exploration of Fagin and the grotesque! I really appreciate your conclusion that there may be a path towards redemption through the regernerative quality of the grotesque. That’s a useful framework to work through ambivalent feelings about many other characters that are read as offensive in the present. Maybe we can extend the communal body to the fictional, seeing them as an extension of our collective spirit. As cultural norms and values evolve they evolve too. Critcal analysis of characters like Fagin is necessary because in many ways they are still with us.

It has been a long time since I have seen the movie Oliver and this brought back a lot of memories from music class when I was in Elementary school. It is very interesting how you chose to look at this through a Bakhtinian lens especially how the anti semitism is employed through many aspects of the grotesque in Fagin’s character. It is also interesting how Fagin’s character changed with the times as people became more conscious about anti semitic attitudes and stereotypes.