Hi, everyone! Today I want to introduce the grotesque facade in Chinese culture from the novel A Journey to the West. It is one of the most famous classical Chinese novels written by Wu Cheng’en during the 16th century. The novel is based on the actual 7th-century pilgrimage of the Buddhist monk Xuanzang to India in search of Buddhist scriptures. The novel can be read as an adventure tale and satire, but the journey and the goal are Buddhist. In comparison, Wu Cheng’en exhibits a carnivalesque and grotesque world that is the opposite of the tranquil Buddhist world.

In the 100 chapters of the book, Xuanzang travels through the world full of monsters and degraded mythical creatures and defeats them with his three monster-like disciples. Xuanzang is vulnerable and weak, and he is no match for the evil creatures seeking to kill and eat him (his flesh is known as an elixir which imparts immortality). And so the bodhisattva Guanyin(literally means “Goddes of Mercy”) arranges for an eclectic group to become his disciples and protect him: the valiant but impetuous Monkey, the lustful Pigsy, and the taciturn Monk Sand. All the disciples have been banished to the human world for sins in the heavens. Out of mercy, Guanyin gives them one more chance to return to their celestial home: They can convert to Buddhism and protect Xuanzang on his pilgrimage.

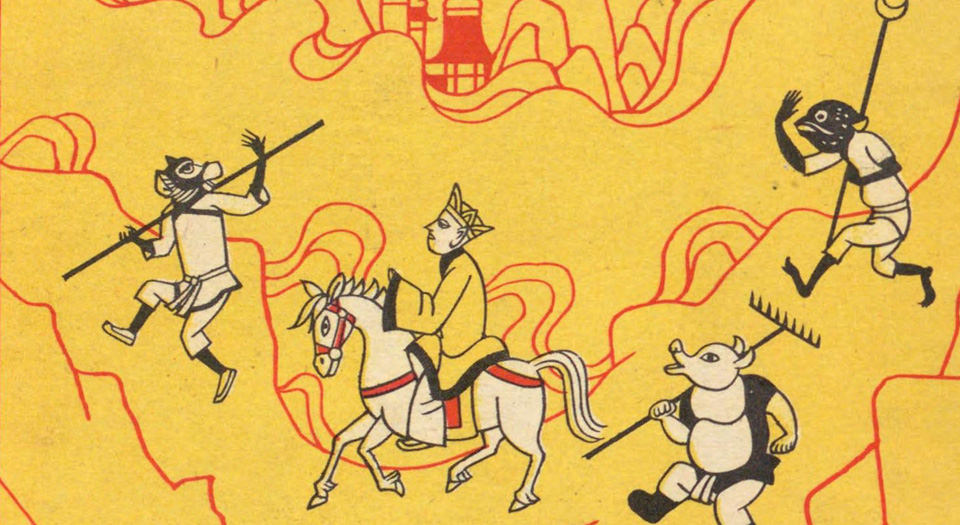

(Print of A Journey to the West.)

(Graphic novel of A Journey to the West.)

(The 1986 TV series of A Journey to the West.)

The world in A Journey to the West is dominated by monsters. Most of the monsters have faces of beast and bodies of humans, and they use the same language to communicate with humans. These monsters can be roughly divided into three categories:

- Animals that transform into human shape after long-term self-trainings;

- Gods/goddesses and divine creatures banished from heaven to the human world(like the three disciples of Xuanzang);

- Divine creatures that willingly degraded themselves.

(The Seven Spider Monsters; 1st category. From the 1986 TV series.)

(The White Elephant; 3rd category. From the 1986 TV series.)

The behavior of monsters is not controlled by rules and regulations of both heaven and human society, so the monsters generally behave arrogantly, especially the third type of monsters: the Divine Creatures. They are dissatisfied with being under the control of gods or Buddhas in heaven, so they voluntarily degenerate into monsters in the human world in order to gain the position above human beings with their divine power.

Monsters rarely survive alone. Most of the monsters will summon hundreds of other monsters and occupy a relatively large area as their territory. When humans or creatures not belonging to their company break into their territories, these monsters will hunt them for food. Moreover, intemperance is the normal state of monsters; for them, indulgent drinking and overeating, as a way of life contrary to human routines, show their power. This independence from human society creates radically different values. Monsters don’t care about money or self-cultivation, but they praise noise, gore, and filth which cause fear and obedience.

Questions:

- Does the worldview of A Journey to the West remind you of Bakhtin’s points? What elements in this book are grotesque or carnivalesque according to Bakhtin?

- A Journey to the West depicts this pilgrimage from a secular perspective, so does the inclusion of religion make this story more grotesque and carnivalesque?

- Does A Journey to the West remind you of any material we have read before? Is there any similarity between them?

Thank you very much for reading! Since this book is completely about Chinese culture, I tried to explain it clearly. If you have questions about any details, feel free to tell me in your comment, and I will answer them immediately!

Hi Eve! I think this is a very cool and relevant appetizer. In response to your questions:

1) I’m initially struck by how carnivalesque the society of monsters sounds. I’m fascinated by the fact that the monsters feel a need to be surrounded by other monsters; unlike human society where the carnivalesque is potentially an escape, the monsters demand it as their constant state of being. I also think it’s interesting to note that a very clear distinction (and perhaps juxtaposition) seems be drawn between the monsters and humans.

2) For this question, do you mean that if religion were to be included, would it be more carnivalesque, or are you asking if the fact that it’s satire of a religious story makes it more carnivalesque?

3) I’m mainly basing this off of the images, but they really strongly remind me of the Satyricon and the Aristophanes plays. The image from the 1968 tv series of people standing together remind me pretty strongly of costume given to the actor character in the beginning of the Satyricon. It also reminds me of the images that (I think Hannah?) showed in an appetizer earlier this year on Aristophanes.

Great job with the first online appetizer! I think your content is very interesting and you did a great job explaining the narrative and including relevant images to help us picture the story.

Hi Eve,

I think this appetizer is very interesting and applicable to what we are focusing on in class. In thinking about the divine monsters, the monsters that come down from heaven to avoid control of the gods and control humans, do they all remain equal on earth? In other words, are there any dominant monsters or a ranking system? This got me thinking about how the carnivalesque facilitates the removal of hierarchy, and it seems that the monsters are also trying to do this. But once they achieve freedom from the power in the heavens, do they remain equal?

These monsters remind me of monsters in greek mythology, and how sometimes they can show up on earth as well.

This is really cool! I actually remember stories from the series from when I was a child. Responding to your third question, now that I think about it, Journey to the West reminds me of the Satyricon (particularly the film). Now that I look back at photos of Journey to the west the behavior of the monsters and even the main characters are not constrained, and in many ways are chaotic and messy. The story stumbles and fumbles around and things are often nonsensical and unpredictable.

I also agree with Jake’s point that the pig character reminds me of one of the opening scenes of the Satyricon where the actor is wearing a pig mask! The nature of the monsters and characters is grotesque, and it is a great parallel to Fellini. Something that I love in both works is how the monsters/ characters bask in their grotesque costumes/ appearances and you can tell how much they are enjoying their roles and embracing the notion of the grotesque even if it is just for the screen.

Hi, everyone! Thanks a lot for your thoughtful comments, and I’m glad you like this topic! First I will answer some of the questions you had for the first post.

1. Hierarchy and ranks do exist in the companies of monsters. However, it varies from the hierarchy of the human world in a bizarre way. Monsters like the White Elephant have more power and abilities so that they become the leaders of other 1st category monsters who are more vulnerable. The leader monster takes the responsibility to maintain the peace within the society; in some chapters, the leaders even promise all the monsters a share of Xuanzang’s flesh so they all get access to eternal life(This is kind of similar to the social structure we saw in Aristophanes’ peace). Each monster has his/her unique job, and the individual monster is always proud of his/her labor because the work makes him/her an important member of the group. Moreover, the division of class among monsters is very ambiguous. In Chapter 74, it is said that a monster can get a promotion just for making a good cooking fire. Consequently, it seems to me that the practice of hierarchy in monster societies is a way of imitating humans, and the only clear division of class is between the sole leader and all the other monsters.

2. About my second question regarding religion, I was thinking about the satire of this religious story. As Xuanzang and his disciples travel through this grotesque world to approach the essence of Buddhism, we cannot ignore two facts: first, many monsters degrade willingly from the destination of Xuanzang; and second, the three disciples are actually monsters, too.

And Jake’s point on the distinction between humans and monsters pushed me to think about the nature of this story. It is actually hard for me to tell whether the author attempts to focus on the distinction or to expose the true and original nature of humans and gods. As you can see from the pictures and my description, the monsters have a motivation to act like humans. While the 1st category monsters spend thousands of years to get rid of the bestial bodies, the 2nd and 3rd category monsters also insist on the human shapes and adapt some of the social structures of the human world. The strict human society and religion of ancient China reflected in A Journey to the West do not allow carnivals to happen, then can we take the carnivalesque lifestyle of monsters as an inner desire of humans and Buddhists?

P.S. I am glad that you mentioned Satyricon and the pig mask, and I just want to add something I did not mention in the first post that Pigsy’s origin can be traced to the stereotyped foolish adjutant figure in early Chinese drama most often performed in the marketplace.

Thanks for getting back to me about the hierarchies of monsters. Knowing now that they recognize rank, would it still be safe to classify as carnivalesque? More broadly speaking, can the carnivalesque exist while one of the aspects of its definition is challenged?

That’s a really interesting question that also crossed my mind when I was reading Eve’s comment. I would argue that hierarchies are not conducive to the carnivalesque, especially because of the inherent power dynamics that arise when there is a hierarchy. Especially in the case of Journey to the West there are monsters who are inherently stronger than others. However, I do think it’s interesting to imagine if a carnivalesque environment can exist in spirit despite the presence of hierarchy. Does the definition of carnivalesque have to be followed strictly? If it does, does that run contradictory to the spirit of the carnivalesque?

First, I will answer Jake’s question on Thursday. A Journey to the West was banned after its publishment for a long time for its sarcasm to the royal family and blasphemy. Even so, the stories in this book were still widely circulated among the people and loved by them.

Looking back at our discussions over this week, we reached an agreement that this book is about a grotesque and carnivalesque story. The only thing that we are not so sure about is the hierarchy in monster societies because it cannot exist in a carnivalesque environment if we strictly follow the “standard” set by Bakhtin.

I personally think that it is very important to keep in mind that carnival is a concept pointing directly to Rabelais’s era and religious background; however, there is no such identical concept in Ancient China. It is just like what we discussed when we were reading Aristophanes’ Peace that there are significant differences between cultures in different places and eras. Regarding hierarchy in A Journey to the West, I will say that its existence is probably for a long-lasting carnival and eternity of the monster society. But still, I am not even sure, and I have the feeling that my thought would change in the future.