(reposting to resolve a technical issue)

Hi, everyone! For my presentation this week I want to talk about giants and their grotesque bodies. It is not a secret that Rabelais was deeply influenced by Greek and Latin literature. In his book, we can also find references from classical literature and clues of ancient culture. Today, I want to bring your attention to some of the most famous mythological giants(maybe you know them already), and hopefully, they will bring us some new ideas about the giant bodies of Pantagruel and Gargantua.

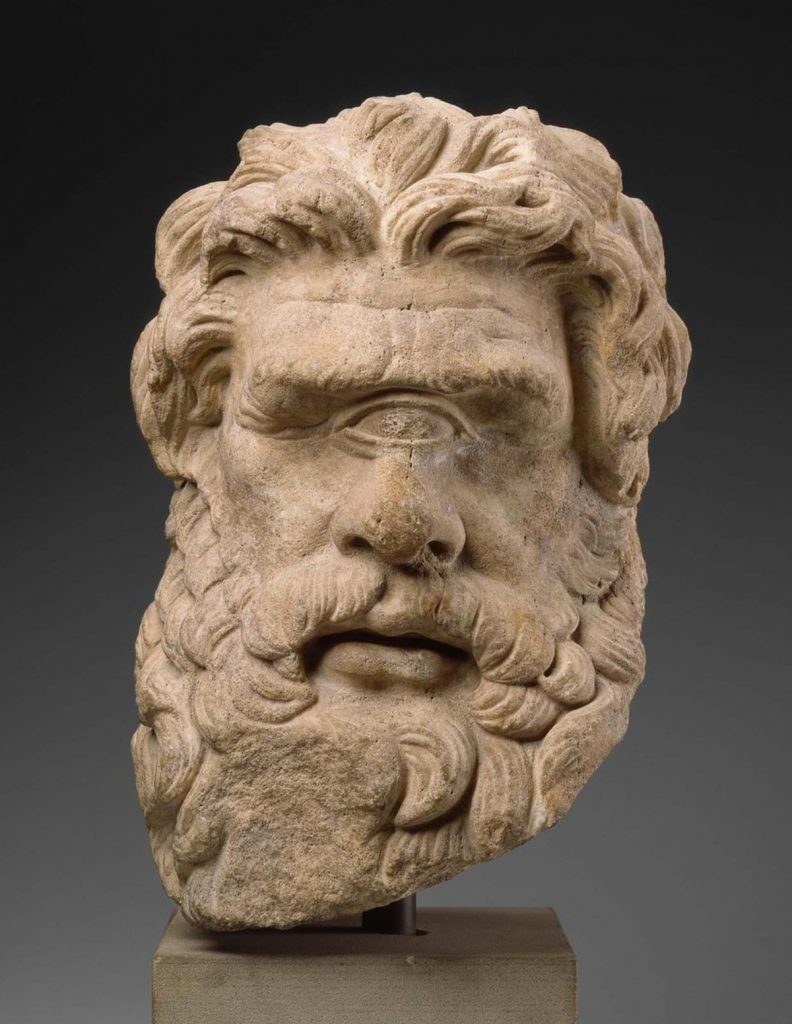

The Cyclopes

Hesiod’s Theogony tells us that the Cyclopes were the children of Gaia and Uranus, and they were the generation before the Olympian gods. The Cyclopes were one-eyed giants who lived in caves and in a simple pastoral lifestyle. They were also depicted as professional builders and blacksmiths with immense physical power.

In Theogony, they are the brothers: Brontes, Steropes, and Arges, who provided Zeus with his weapon — the thunderbolt. In Homer’s Odyssey, they are an uncivilized group of shepherds, the brethren of Polyphemus encountered by Odysseus. The Cyclopes were also written by many Greek and Roman writers like Euripides, Virgil, and Callimachus.

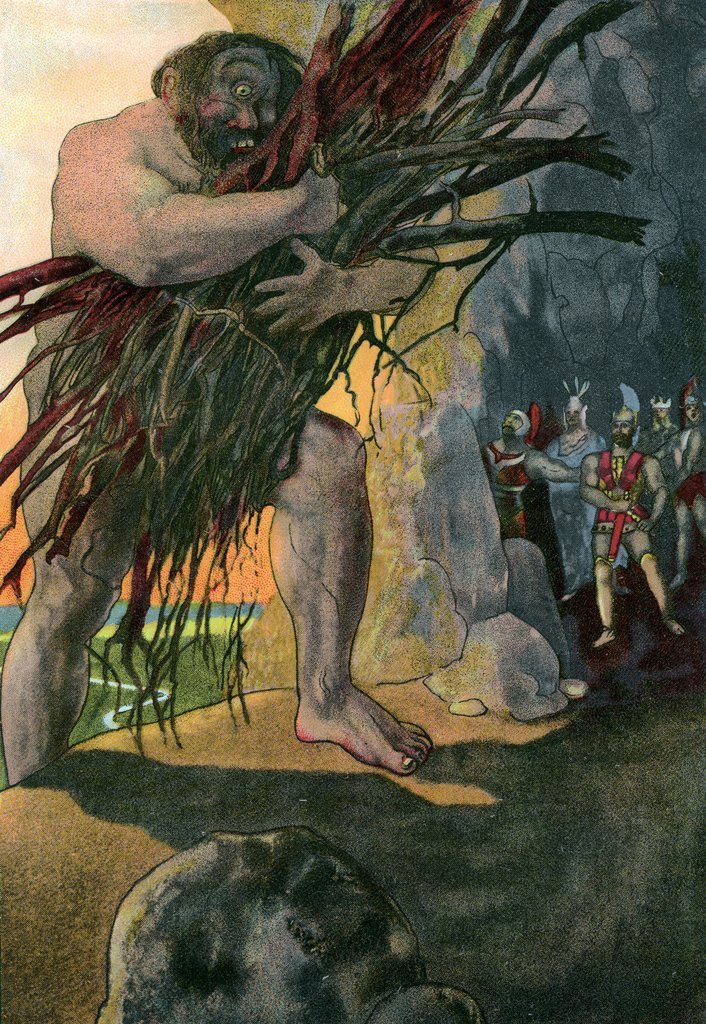

Cacus

Cacus is known as the fire-breathing son of Vulcan, who lived in a cave and committed various kinds of robberies. As Virgil writes in The Aeneid, Cacus stole the cattle of Hercules and dragged them into his cave by their tails, so that it was impossible to discover their traces. But when the remaining oxen passed by the cave, those within began to bellow. Hercules then found the them in the dark cave of Cacus and killed him.

Please read this excerpt from Book VIII of The Aeneid so that you can get an image of Cacus:

But Cacus’s den and his vast realm stood revealed,

and the shadowy caverns within lay open,

no differently than if earth, gaping deep within,

were to unlock the infernal regions by force, and disclose

the pallid realms, hated by the gods, and the vast abyss

be seen from above, and the spirits tremble at incoming light.

So Hercules, calling upon all his weapons, hurled missiles

at Cacus from above, caught suddenly in unexpected daylight,

penned in the hollow rock, with unaccustomed howling,

and rained boughs and giant blocks of stone on him.

He on the other hand, since there was no escape now

from the danger, belched thick smoke from his throat

(unspeakable) and enveloped the place in blind darkness,

blotting the view from sight, and gathering

smoke-laden night in the cave, a darkness mixed with fire.

(Translation by A. S. Kline)

Now let’s look back to Rabelais. From the beginning of Rabelais’ book, the readers are made aware of how Pantagruel’s gigantic size affects the imagery of the narrative. Practically everything used to feed and clothe him is visually described in immense detail. Readers are informed that hundreds of cows produce milk to feed baby Pantagruel, and fetters are used to control this extremely powerful infant. Although his size creates amazing visuals throughout the narrative, it also seems to change frequently throughout the books. Pantagruel is able to go into any random building and travel through cities without many obstacles impeding his movements, even though he shouldn’t fit in these settings. These ambiguities in the book make Pantagruel’s giant identity more interesting and worth thinking about.

Questions:

- Why is Pantagruel a giant? Is it necessary for Rabelais to make Pantagruel a giant?

- What abilities are given to giants to make them different from humans?

- Pantagruel does not have a huge eye on his forehead or the ability to breathe fire; he is a giant with human appearance and habits. Do you still find him similar to the mythical giants?

The first question you asked is particularly interesting and difficult to answer. I feel like Bakhtin understands his giantness as the pinnacle of the grotesque body, with its exaggeration and size and imposition upon others in a positive aspect, but Rabelais had no idea that Bakhtin was going to theorize Pantagruel in that way, so it’d be negligent to just say that he is a giant to accomplish grotesque/carnivalesque ends.

In a way, that the novel is about a giant is the *premise* of the series/novel itself, and it might be more efficient to wonder why that premise was/is so compelling for consumers. I can only speculate on that point, but there are generally two theories about why stuff is funny: we laugh because we feel better than the thing we’re laughing at vs. we laugh because the thing we’re laughing at is unexpected. (The prepositions here are finicky.) A really really huge guy, without the features of mythical giants (just a huge guy), is funny and compelling because it breaks the entire world open to the potential for incongruity (in contrast to our day-to-day) while mocking the status quo, which I think Collin may have mentioned in the reading diary at some point as a facet of Rabelais’ humor. The unexpectedness of the size of giants can also be terrifying (as your examples and several episodes in Rabelais show), but it can often be exploited to comic effect.

Pantagruel does not have the powers of some other giants. He is not mythical but as you said a regular guy. I agree in that him being a giant serves as a comedic effect. He has no powers but simply having a giant among regular people is funny at times due to the absurdity in some scene. Sometimes while reading I forgot that he’s a giant and this adds another layer of carnivalesque laughter to the text. Are there any other reasons for having Pantagruel be a giant because this one makes most sense to me?

Pantagruel is pretty different from mythical giants. We tend to expect them to be lumbering beasts. As we see in your summaries of mythical giants, they do extraordinary things and tend to be villainous. Pantagruel does not fit these descriptions. He is virtuous and educated, very out of character with other examples throughout history.

I think Pantagruel being a giant is somewhat necessary to the story. My mind could be changed on this, because often I forget he’s a giant as I read, but I think that the absurdity of this novel is what drives it. I do think the novel could still be successful and entertaining if Pantagruel wasn’t a giant, but the one of the novel’s primary themes is it’s casual absurdity. It makes huge exaggerations and pretends like they’re commonplace. I think Pantagruel is the epitome of this. He has all of these absurd accomplishments but somehow they’re slightly normalized or expected because he’s a giant.

I agree that the novel could be successful if Pantagruel wasn’t a giant, but then it’d (obviously) be a different novel, and maybe one that Bakhtin’d care less about. I guess, amending my earlier statement that it’d be “negligent to just say that he is a giant to accomplish grotesque/carnivalesque ends,” it might not be negligent to say (from a Bakhtinian perspective) that Pantagruel is giant because this was an inheritance of Rabelais’ from folk humor. It’s kind of like trying to figure out what the Cyclopes are giants, though: they just *are* giants because that’s their folkloric identity. It might be a similar situation with Pantagruel, only that his folkloric identity is always conflated with feasts and parties and Carnival, etc.

It is really helpful that you mentioned the comic effect and folkloric identity of Pantagruel’s gigantic body! And I really like Helena’s point on the surprise from unexpected things. Having read the chapter about Pantagruel’s childhood, I was personally always expecting this novel to be more violent and catastrophic because of the strength of his huge body; however, the unexpectedness keeps breaking my imagination and makes me think of Pantagruel as a comic character.

Moreover, I think it is also important that the world in Rabelais novel is full of people with different identities and various bodies: giants, dwarfs, swindlers, scholars, etc. Pantagruel is just one of those grotesque bodies; however, being a giant, he is probably the most conspicuous and influential one among them. Quite the contrary, the mythological giants are isolated, and they don’t live in such a complex society with all the different identities. So, if we compare these two types of giants, does the lack of carnival cause the image of mythological giants to be scary rather than comic?

Yeah mythological giants are much more scary because they are often isolated and someone comes across on while on a mission to find something. Since these mythological giants are isolated they tend to lack the human behavior that would make them more familiar. These giants often eat humans and people are afraid of them due to their overwhelming size, power and sometimes special powers. Unlike them Pantagruel is a human but just a giant. He shares the human connection that lacks with the isolated giants which allows him to have the carnivalesque spirit.

Your comment reminds me of the discussion we had in Alice’s appetizer group about horror and the grotesque. Thinking about the isolation of the subject might be another way into understanding how horror is different from the grotesque/carnivalesque– the subject themselves are inherently, however we understand that, removed from the fabric of the social space. In contrast, Pantagruel and the many other unusually embodied characters in Rabelais’ novels are inherently a part of the fabric of the social space, conspicuous within a context of community instead of existing outside that community by default. If he was a giant who lived alone in cave on an island, even if he was very kind and nonviolent, wouldn’t be the same for lack of the social, communal aspect of Pantagruel’s life.

I think this is an interesting comment. It’s as if we get some validation by our fictional peers that Pantagruel is not someone to be afraid of (unless you’re attacking Utopia), but rather just an esteemed member of society. Even if they aren’t real, it’s as if we’re influenced by the social pressure of our narrator and peers of whatever movie/novel/story we’re reading/watching to feel the way that they feel too.

I want to thank everyone for the wonderful comments this week. The mythological images are relatively obscure, and as modern audiences, it may be difficult for us to find the ideology that the ancients wanted to express through giants. However, by juxtaposing the mythological giants with the giants in Rabelais’ novel, I believe we all have a deeper understanding about the grotesque body.

The size of giants and the identity itself do not seem to be the origin of the carnivalesque atmosphere in Rabelais’ world; it is more of a road sign that leads us to the core and essence of this particular society. Pantagruel and Gargantua are part of this society, and they also serve as representatives of this society, just as Bakthin mentioned about the relationship between individuals and crowds. Without this group full of different grotesque bodies, the image of giants is meaningless to the world in the book. This again reminds me of how important the gathering is for carnivalesque literature, and it also made me think again how different the grotesque bodies could be without a carnivalesque atmosphere.